Beauty Will Save the World

April 28, 2020

________

In all that awakens within us the pure and authentic sentiment of beauty, there is, truly, the presence of God. There is a kind of incarnation of God in the world, of which beauty is the sign.

–Simone Weil

________

Anxiety. Anger. Fatigue. Grief. And now, we even sense our and others’ desperation—faint or abject as it may be—in the face of the spring of our discontent. I have written earlier about our encounter with this virus, and our bodies’ and hearts’ responses to it. But here I want to invite us to turn our attention to something more hopeful, something to which Dostoevsky was getting at when one of the characters in his novel The Idiot uttered the words that are the title of this essay. Something we desperately need, but that will likely require work on our part nonetheless.

Many reading this may be familiar with Vedran Smailovic, the cellist who, for 22 uninterrupted days in May and June of 1992 played Albinoni’s Adagio in G minor in the ruins of Sarajevo, following a mortar shelling that killed 22 people in a market in the besieged city. He played in the crosshairs of snipers and artillery gunners, and amid the rubble of his town. When all around him tragedy and affliction was the only daily story—with no end to it in sight—his response was to create and offer beauty. Not anxiety. Not fury or revenge. And not despair. Beauty. And the beauty that he offered changed everything.

And by changed, I don’t mean it stopped the shelling. The siege would continue for nearly four more years, and many would lose their lives. One could argue, in fact, that nothing changed at all. But what Smailovic’s commitment to beauty did was to change the direction and trajectory of people’s attention and action. And this is what it will do for us.

We Christians believe that God created human beings in his image. To bear our creator’s image implies many things, not least our depth of desire to be known, such that we may be loved, just as God longs to be known and loved. But our desire does not stop there. For just as God made us to bear his image in our desire to be known, by extension he also made us to do so in our desire to create, even as he creates. And whether we are three years old, or fifty-three, when given the chance, we long to create icons of beauty. We aren’t interested in making dysfunctional or ugly things. When given the option, we want what we make to be elegant and good, be that a garden, a game or a business plan. Sure, we can—and often do—settle for mediocre; but that is not what we want. We want beauty and goodness.

To “have dominion over the earth” is not to rule it with an iron fist or merely to keep an inventory of all the stuff that is warehoused in it. Nor is it to use it at our whim as we please. It is to steward all of its resources in a way that enables the earth and all of its inhabitants to flourish. We were made then, as a function of being known, to create beautiful farms, friendships, software, public policy, sculpture, highways, soufflés, architecture, poetry, furniture, marriages—you get the picture—such that these icons of beauty and goodness circle back around to further enhance our experience of being known and loved. Further up and further in, perhaps, as Lewis might say.

Now, some would argue that beauty is really just a luxury. It’s an add-on, it’s not a necessity. To consider beauty isn’t really “getting things done,” or “being productive.” But here’s the thing. Just because we are besieged by COVID-19 does not mean that our raison d’etre has changed. Our motivation for working so hard to fix the COVID-19 problem is so we can regain a life in which we are able to experience joy in the presence of others’ embraces; in which we take pleasure in the goodness of gathering for worship and for meals at our favorite restaurants; and in being moved by a live symphony; in which, in essence—we are able, at last to once again be immersed in beauty. And when eventually we look back and tell the stories of the work of those on the front lines treating patients or developing a vaccine for the virus, we will tell them not only in terms of heroism, but in terms of the elegance, the deftness, the skill—the beauty—that all of that work entailed.

Deep in our souls, despite our social distancing, we still long to be connected in order for us to create beauty in the infinite number of ways that God has placed at our disposal in order to enable the entire creation to flourish, not least for our own souls to be nourished by it. Hence, our present travail is not merely due to our disabled capacity to share embodied space. It is a function of the interruption of our primally endowed impulse to create beauty in the presence of and for others. Amidst the shelling from the virus, we are called to plant ourselves firmly in the rubble and play the cello.

You may wonder if this is just an empty wish, a pipe dream. But you would be wrong. And fortunately, there are things we can do.

First, as some of you already have, begin to make it a habitual practice of engaging in some creative action at least two to three times a week. I have highlighted this before (see No. 8), but I cannot overemphasize it here, now that we have a better sense of what extended separation from others and our normal creative outlets feels like. This can be as “simple” as trying out a new recipe; pulling weeds in your garden; coloring with your child; watching a video instructing you how to begin to draw; beginning to read a critically acclaimed biography; planting flowers or herbs; writing in a journal about your reflections of the day. These are examples of how we can actively engage our brain’s right hemisphere’s mode of attunement to the world, the mode that keeps us temporally engaged in the present moment. Moreover, these acts of creativity give us a sense of agency, of acting in this world that, for the moment in which we are creating, changes it by focusing our attention on beauty, and in this case, the beauty that begins to emerge when we create something, no matter how elementary it may seem.

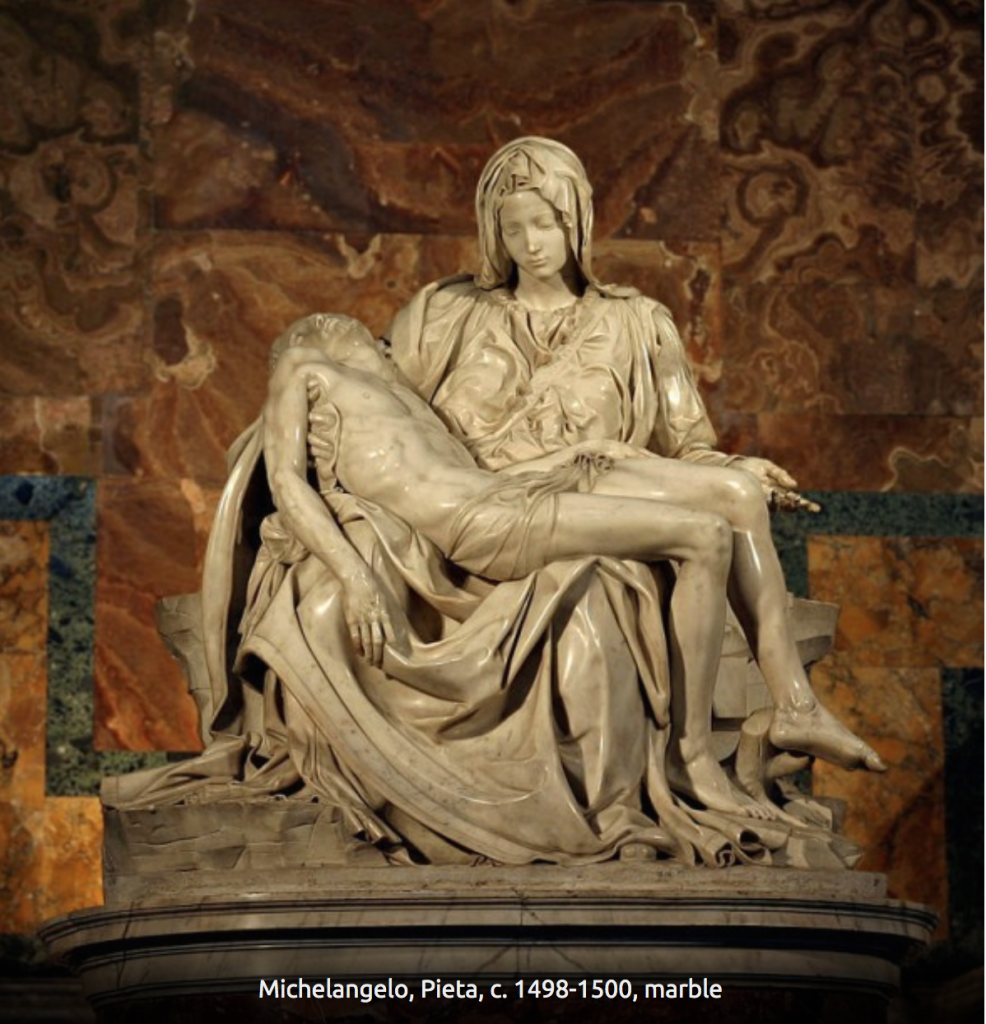

Second, practice putting yourself in the path of oncoming beauty. In other words, make time to engage art that has stood the test of time, be that music, painting, sculpture or poetry to name but a few forms available to us. Although you can’t make it to your local museum, you can find beautiful artistic offerings on the Internet with ease. Of course, it is not the same as seeing it in the National Gallery of Art, but it is not nothing. You could, for instance, view Rembrandt’s The Return of the Prodigal Son, Michelangelo’s Pieta or listen to a choral arrangement of Psalm 8. Plan to spend at least twenty to thirty minutes simply being with what you are seeing or hearing, and allow yourself to be met by them. Then (predictably), write reflections of what you have experienced.

Another way of putting yourself in the path of oncoming beauty is to make time, if even only a few minutes, to be in touch with the creation. Consider, for example, beginning each day, as my friend Andy Crouch has suggested, by encountering nature before you look at any device. That’s right. Before you look at your phone or your tablet or laptop, go outside. Even if it’s raining (in which case, allow yourself to be touched by the rain). Take at least five to ten minutes to look around at anything that is living—a tree is an easy choice—and approach it. Look at it; be curious about it; touch it (okay, maybe not if it’s in your neighbor’s back yard); allow yourself to feel your hand feeling what you are touching. Notice its beauty—and be aware that you did not create this. This object was made with you in mind, for your enjoyment, to nourish your soul and for you to steward. It is God winking at you, reminding you that he is alive and active in the world and is still in the business of creating goodness and beauty—even in the presence of a pandemic—and wants you to join him.

Third, as I have also mentioned elsewhere, plan to connect with others with regular frequency with the intention of informing them of what creative act you have committed or how you have allowed yourself to be found by beauty in nature. In a conversation I was part of recently with a number of my close friends, one of them mentioned that one day in the past week he had done some work in his garden, as he seemed to have the time. Later that day he discovered a pileup of work in the form of emails that had somehow magically accumulated while he was off doing something creative and that nurtured his soul—working the soil of his garden. He spoke of how he worried that he should have been more attentive to his computer rather than be in his yard. Not only did the rest of us assure him that the work he did in his garden was good for his soul, it was also necessary that he be in the business of creating beauty in that domain of his life in order to live effectively in his life at the work that earned him his paycheck. However, mostly, we wanted him to know that if ever he doubted that creating beauty as he did was acceptable, we wanted to be the first people he called to assure him that it is—not only because we need to be reminded of the same thing; but because our relational connection itself is an expression of beauty against which no siege against our souls can prevail.

It is tempting to think that playing the cello in the face of snipers and artillery guns is mere folly, and that in the real world, the world of violence, beauty has no power whatsoever. But beauty is exactly what God gave us in Jesus. He entered a world that eventually surrounded him, putting him in its crosshairs and on its cross. And like Smailovic, he remained. But it was Beauty, not death, that had the final word. In this time of COVID-19, a time of violence against humanity, we must remember that, just as the hideousness of crucifixion gave way to the irrepressible beauty of Easter, so we must look for and live in resonance with that very oncoming beauty, putting ourselves in its path such that it will save our lives and the life of the world, one sidewalk chalk painting at a time.